Network Protocol Breakdown: Ethernet and Go

If you’re reading this article right now, chances are pretty good that there’s an Ethernet (IEEE 802.3) link somewhere between your device and the server hosting this blog. The Ethernet family of networking technologies are a fundamental building block in many of today’s computer networks.

There is a great deal to be said about how Ethernet works at the physical level, but this post will focus on Ethernet II frames (“Ethernet frames”): the Layer 2 frames that enable communication between two machines over an Ethernet link.

This post will break down the structure of Ethernet II frames in detail,

explaining the significance of each item within the frame. We will also discuss

how to make use of Ethernet frames in the Go programming language, using

github.com/mdlayher/ethernet.

Introduction to Ethernet frames

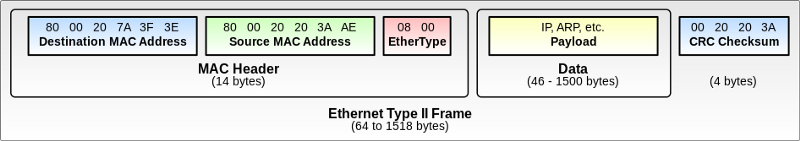

The fundamental unit of Layer 2 data transmission for Ethernet networks is an Ethernet frame. The frame’s structure is rather straightforward, compared to some more complex protocols built on top of it.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethernet_frame#Ethernet_II

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethernet_frame#Ethernet_II

The first two fields in an Ethernet frame are the destination and source MAC addresses. A MAC address is a unique identifier for a network interface on given Layer 2 network segment. Ethernet MAC addresses are 48 bits (6 bytes) in length.

The destination address indicates the MAC address of the network interface which

should receive a given frame. In some cases, this may be the Ethernet broadcast

address: ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff. Some protocols, such as ARP, send frames with a

broadcast destination in order to send a message to all machines on a given

network segment. When a network switch receives a frame with the broadcast

address, it duplicates the frame to each port attached to the switch.

The source address indicates the MAC address of the network interface which sent the frame. This enables other machines on the network to identify and reply to messages received from this machine.

The next field is a 16 bit integer called the EtherType. The EtherType indicates which protocol is encapsulated in the payload portion of a given frame. Some typical examples include Layer 3 protocols such as ARP, IPv4, and IPv6.

The payload of an Ethernet frame can contain anywhere from 46 to 1500 (or more!) bytes of data, depending on how the machines on a Layer 2 network segment are configured. The payload can carry arbitrary data, including the headers for Layer 3 and above protocols (which may even encapsulate traffic at higher layers).

The last element of an Ethernet frame is the frame check sequence (“FCS”): a CRC32 checksum using the IEEE polynomial which enables detection of corrupted data within the frame. Once the frame is assembled, the checksum is computed and stored in the final 4 bytes of the frame. Typically, this is done automatically by the operating system or network interface, but in some circumstances, it is necessary to compute the FCS in userspace software.

Crafting an Ethernet frame in Go

Using the ethernet package, Ethernet

frames can be created in Go and used to send and receive data over a network.

In this example, we will create a frame that carries a minimal “hello world”

payload with a custom EtherType. The frame will be broadcast to all machines on

the same Layer 2 network segment, using the Ethernet broadcast address:

ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff.

// The frame to be sent over the network.

f := ðernet.Frame{

// Broadcast frame to all machines on same network segment.

Destination: ethernet.Broadcast,

// Identify our machine as the sender.

Source: net.HardwareAddr{0xde, 0xad, 0xbe, 0xef, 0xde, 0xad},

// Identify frame with an unused EtherType.

EtherType: 0xcccc,

// Send a simple message.

Payload: []byte("hello world"),

}

// Marshal the Go representation of a frame to the Ethernet frame format.

b, err := f.MarshalBinary()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to marshal frame: %v", err)

}

// Send the marshaled frame to the network.

sendEthernetFrame(b)

As mentioned earlier, the operating system or network interface will typically

handle the FCS calculation for the Ethernet frame. In unusual cases where this

cannot be done automatically, the MarshalFCS method can be invoked to append a

calculated FCS to the marshaled frame.

Introduction to VLAN tags

If you’ve worked with computer networks in the past, you may be familiar with the concept of a VLAN: a Virtual LAN segment. VLANs (IEEE 802.1Q) enable splitting a single network segment into many different segments, through clever re-use of the EtherType field in an Ethernet frame.

Source: http://sclabs.blogspot.com/2014/10/ccnp-switch-vlans-and-trunks.html, note: CFI has now been re-purposed as Drop Eligible Indicator (DEI) instead.

Source: http://sclabs.blogspot.com/2014/10/ccnp-switch-vlans-and-trunks.html, note: CFI has now been re-purposed as Drop Eligible Indicator (DEI) instead.

When a VLAN tag is added, the 16 bit EtherType field becomes the Tag Protocol

Identifier field. This indicates that a VLAN tag is present, using a reserved

EtherType value such as 0x8100.

When a VLAN tag is present, the 16 bits immediately following it designate three fields:

- Priority (3 bits): an IEEE P8021.p class of service level.

- Drop Eligible Indicator (DEI; formerly CFI) (1 bit): indicates if a frame may be dropped in the presence of network congestion.

- VLAN ID (VID) (12 bits): specifies the VLAN to which the frame belongs. Each VID creates a unique network segment.

After the VLAN tag, the EtherType which indicates the encapsulated traffic is present, as normal.

In some circumstances, multiple VLAN tags may be present (IEEE 802.1ad), also known as “Q-in-Q”). As an example, this enables an internet provider to encapsulate a customer’s traffic in a single VLAN, while the customer may also encapsulate their own traffic in many different VLANs.

Specifying VLAN tags for Ethernet frames in Go

Often, the network interface will take care of VLAN tagging for Ethernet frames, but in some circumstances, it can be useful to apply this tag in software as well. Let’s specify a VLAN tag manually, using the frame from our prior example.

// The frame to be sent over the network.

f := ðernet.Frame{

// Broadcast frame to all machines on same network segment.

Destination: ethernet.Broadcast,

// Identify our machine as the sender.

Source: net.HardwareAddr{0xde, 0xad, 0xbe, 0xef, 0xde, 0xad},

// Tag traffic to VLAN 10. If needed, a ServiceVLAN tag can be applied

// for Q-in-Q.

VLAN: ðernet.VLAN{

ID: 10,

},

// Identify frame with an unused EtherType.

EtherType: 0xcccc,

// Send a simple message.

Payload: []byte("hello world"),

}

In my (admittedly limited) experience, the Priority and DEI fields in the VLAN tag are not generally needed. If in doubt, leave them set to zero.

Sending and receiving Ethernet frames over the network

Most network applications typically build upon TCP or UDP, but since Ethernet frames operate at a much lower level in the stack, some special APIs and permissions are required to make use of them directly.

On Linux, this API is referred to as “packet sockets” (AF_PACKET). These low

level sockets enable sending and receiving Ethernet frames directly, using

elevated privileges from the operating system.

On Linux and BSD, github.com/mdlayher/raw

can be used to send and receive Ethernet frames over a network interface. Here’s

an example that shows how to broadcast our crafted Ethernet frame with its

“hello world” message:

// Select the eth0 interface to use for Ethernet traffic.

ifi, err := net.InterfaceByName("eth0")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to open interface: %v", err)

}

// Open a raw socket using same EtherType as our frame.

c, err := raw.ListenPacket(ifi, 0xcccc, nil)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to listen: %v", err)

}

defer c.Close()

// Marshal a frame to its binary format.

f := newEthernetFrame("hello world")

b, err := f.MarshalBinary()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to marshal frame: %v", err)

}

// Broadcast the frame to all devices on our network segment.

addr := &raw.Addr{HardwareAddr: ethernet.Broadcast}

if _, err := c.WriteTo(b, addr); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to write frame: %v", err)

}

On a different machine, we can use a similar program to listen for incoming Ethernet frames using our specified EtherType.

// Select the eth0 interface to use for Ethernet traffic.

ifi, err := net.InterfaceByName("eth0")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to open interface: %v", err)

}

// Open a raw socket using same EtherType as our frame.

c, err := raw.ListenPacket(ifi, 0xcccc, nil)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to listen: %v", err)

}

defer c.Close()

// Accept frames up to interface's MTU in size.

b := make([]byte, ifi.MTU)

var f ethernet.Frame

// Keep reading frames.

for {

n, addr, err := c.ReadFrom(b)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to receive message: %v", err)

}

// Unpack Ethernet frame into Go representation.

if err := (&f).UnmarshalBinary(b[:n]); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("failed to unmarshal ethernet frame: %v", err)

}

// Display source of message and message itself.

log.Printf("[%s] %s", addr.String(), string(f.Payload))

}

That’s it! If you’d like to give this a try at home and have two or more Linux

or BSD machines available, you can try out my etherecho

demo binary.

Summary

Low-level networking primitives like Ethernet frames and raw sockets are very powerful. Using these primitives, you can have complete control over the traffic sent and received by your application.

If you find these types of programs as exciting as I do, I highly encourage you

to take my ethernet and raw

packages for a spin. In future posts, I’ll discuss some of the protocols you can

build directly on top of Ethernet frames and raw sockets.

Thank you very much for reading this post. I hope you’ve enjoyed it and learned something new along the way. If you have, you may also be interested in some of my other posts about using low-level networking primitives with the Go programming language.

Finally, if you have questions or comments, feel free to reach on Twitter or Gophers Slack (username: mdlayher).

Thanks again for your time!

Links

- Package

ethernet: github.com/mdlayher/ethernet - Package

raw: github.com/mdlayher/raw - Command

etherecho: https://github.com/mdlayher/ethernet/tree/master/cmd/etherecho